- Entry, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture

- Low oblique aerial view of Standing Rock with Navajo fields in Canyon Del Muerto in Canyon De Chelly National Monument in afternoon light. This view is an attempt to rephotograph the 1929 Charles Lindbergh aerial photograph, negative #130255.

- Standing Rock,1929 Charles and Anne Lindbergh

- White House from Afar, 1929. Charles and Anne Lindbergh, 1929

- Aerial view of Chinle Creek and the isolated red rock fin near White House Ruin in Canyon De Chelly. This view is to the northwest in afternoon light, with Round Rock and Little Round Rock on the horizon. This view is an attempt to rephotograph the 1929 Charles Lindbergh aerial photograph, negative number 130246. Adriel Heisey

- Oblique aerial view of Pueblo Del Arroyo along Chaco Wash in Chaco Canyon, looking north in midday light. This view is an attempt to rephotograph the 1929 aerial photograph by Charles Lindbergh, negative #130199.

- IPAD program, Installation, Museum of Inidan Arts and Culture, Santa Fe NM

- Entry panel, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture

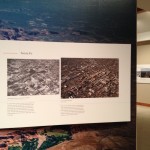

- Santa Fe then and Now, Installation, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture

- Installation, Museum of Inidan Arts and Culture, Santa Fe NM

- Installation, Museum of Inidan Arts and Culture, Santa Fe NM

- Educational area, Installation, Museum of Inidan Arts and Culture, Santa Fe NM

Oblique Views: Southwest Aerial Landscapes by Charles and Anne Lindbergh and Adriel Heisey

During 2007 and 2008, flying at alarmingly low altitudes and slow speeds, Adriel Heisey leaned out the door of his light plane, and holding his camera with both hands, re-photographed some of the Southwest’s most significant archaeological sites that Charles Lindbergh and his new bride Anne photographed in 1929.

Oblique Views: Southwest Aerial Landscapes by Charles and Anne Lindbergh and Adriel Heisey, showcases large prints of Heisey’s stunning images paired directly with the Lindberghs’ photos of the same locales. Archaeology Southwest, whose mission is to explore and protect the places of the past, originally conceived the Oblique Views project in 2004 as a preservation project to scan and protect the 198 deteriorating nitrate negatives of archaeological landscapes and sites shot by the Lindberghs, among the earliest aerial photographs of archaeological sites in the American Southwest. Intrigued by the changes those photographs revealed, they commissioned Heisey to recreate near-exact “now” images that correspond with the Lindberghs’ perspective, time of year, and time of day. The Museum of Indian Arts and Culture later commissioned several more. Taking matching images of an original photograph at a later time illuminates the passage of time, much like the family that lines their kids against the fireplace for a yearly Christmas photo. To know when he had achieved the perfect reproduction, Heisey compared his image, shown on his laptop placed on the seat next to him in the plane’s cockpit, with photocopies of the target Lindbergh photos. The exhibition comprises seventeen pairings of photographs.

In this exhibition, the Lindberghs’ grainy black-and-white shots are a record of how the sites appeared before later excavations, development, or time altered them. Their images are an excellent yardstick for evaluating changes on many levels over the last eighty years, especially when viewed side-by-side with Heisey’s recent photographs.

As Oblique Views shows, aerial photographs expose the connections between the varied elements of landscapes that can be difficult to perceive from the ground. They reveal how ancient people lived in the landscape and accessed resources, where they planted crops, and to a trained eye they also indicate walls, site structures, ditches, residences, and even footpaths. As exhibition curator Maxine McBrinn describes it in Oblique Views: Aerial Photography and Southwest Archaeology, which accompanies the exhibition: “An Oblique View is taken from the side, a perspective that, especially when taken early or late in the day when shadows are long, emphasizes small differences in elevation and can make visible otherwise unseen roads, houses, or other site features.”

Linda Pierce, Deputy Director of Archaeology Southwest said, “By seeking and sharing commentary from Native Americans, landowners, archaeologists, and historians, among others, the Oblique Views exhibition conveys that landscapes are cultural as well as geological, imbued with history and memory.”

Oblique Views is available for three month exhibition to host venues in July 2017 through 2019 and includes 17 large format photographs on wall mounted panels, text and educational materials. Oblique Views then-and-now photographs reveal the layers of civilization of the American Southwest—Native American, Spanish, Mexican, and ultimately Euro-American colonization and settlement—from a vantage point few of us will ever experience.

View a video of several of the then-and-now images here; and an interview with photographer Adriel Heisey here.

The exhibition companion publication, Oblique Views: Aerial Photography and Southwest Archaeology is published by the Museum of New Mexico Press and focusses on the Lindbergh aerial survey, which has never been published and is largely unknown to general audiences.